FEATURED STORY

Attached below is a story that was not included in BAD THINGS HAPPEN, posted here for your enjoyment. In the process of collecting stories for my first book, some had to be left behind, but they are not forgotten! Over the next little while I'm going to be putting up the ones I think people might like to read again, the ones I love the most, and maybe even some of the very weird ones nobody even knows about.

Hope you like them!

KRIS

THE GAME

BY KRIS BERTIN

We come up with the game as a measured response to how bogus everything is.

We’re playing cards and smoking and sweating like crazy—because it’s always hot in his trailer—when Brad tells me he’s doomed. He says he’s set to die or get divorced or disfigured.

He got his fortune told—a full spectrum reading—and the tarot, the I-Ching, the Ouija, and what was left in the bottom of a teacup are all in agreement: he’s fucked at a cosmic level. I tell him what I always tell him, what he says I’m here to tell him—that it’s all bullshit. He’s fucked up and depressed and goes to some gypsy lady—what else is she going to tell him but what he wants to hear? Then he gets into a minor car accident because of poor road conditions, and comes to believe the prophecy is true.

He’s a moron.

You weren’t there, he tells me.

He says that he could feel it.

The thing is, he’s actually a happy guy. As an unhappy person, I know who is and isn’t and I know he shouldn’t be this way. He’s screwed up because his wife and kid were supposed to be here months ago, because he was supposed to have made enough money to move them and all their stuff here by now. Of course, there are things that aren’t entirely his fault, like the fact that he could only get work on this side of the country—a limited-term appointment that seems unlikely to ever turn into anything—or the fact that we get paid monthly, or that Adrienne lost her job back home.

But then there are the things he could help—like drinking, blackjack at the Indian casino, and his mystical consultations. And other things, like his refusal to borrow money from me or the bank or a credit card—the latter two of which he calls the Great Satan.

Because of my DUI, I’m always at his trailer. The couch has become mine, even though my legs hang past the armrest and I always wake up with absolutely no blood in my feet, paralyzed until breakfast. It just makes sense to stay there, because we’re both driving to the same place at the same time to go sit in the same office in the same department. I’m almost never at my own place now, and I am never alone.

It’s better than drinking by myself, and it’s so comforting to be away from my silent apartment and the noise of my own awful thoughts. Also, my father cannot reach me here. The pounds and pounds of pressure his voice exerts aren’t gone, but here I have the luxury of going a week without one of his croaking, demanding phone calls. The pressure is building, I imagine, inside my answering machine.

We start playing the game because I want to cheer Brad up. It’s wrong that he’s depressed, because I have never known him to be. I tell him I’ll give him a reading he can trust, and I have the idea of making up some positive bullshit to counteract the negative. I tell him to go get out his tarot cards or magic dice or pendulums, but he says:

It’s real bad luck to have that shit in your house.

He motions to the unspoiled atmosphere of his living room, which is covered in Masonic skull tapestries and African masks. A dreamcatcher on every window and a wooden box on the coffee table—painted red— where he says his bad thoughts are stored.

You don’t have anything? A divining rod?

No.

I tell him I don’t believe that he has nothing, and after a minute of sipping his Jack Daniels, he gets a can out from between Kachina dolls and a row of KinderEgg toys his kid put together.

It looks like a coffee can, but there are washed-out drawings on it, spirals and stars and little men, turtles and eerie little spirits with horns. Like cave paintings—Hopi petroglyphs—drawn in Crayola marker on brown cardboard. I don’t ask what it’s supposed to mean, I just nod and do what I do best at the trailer. Act like everything is normal.

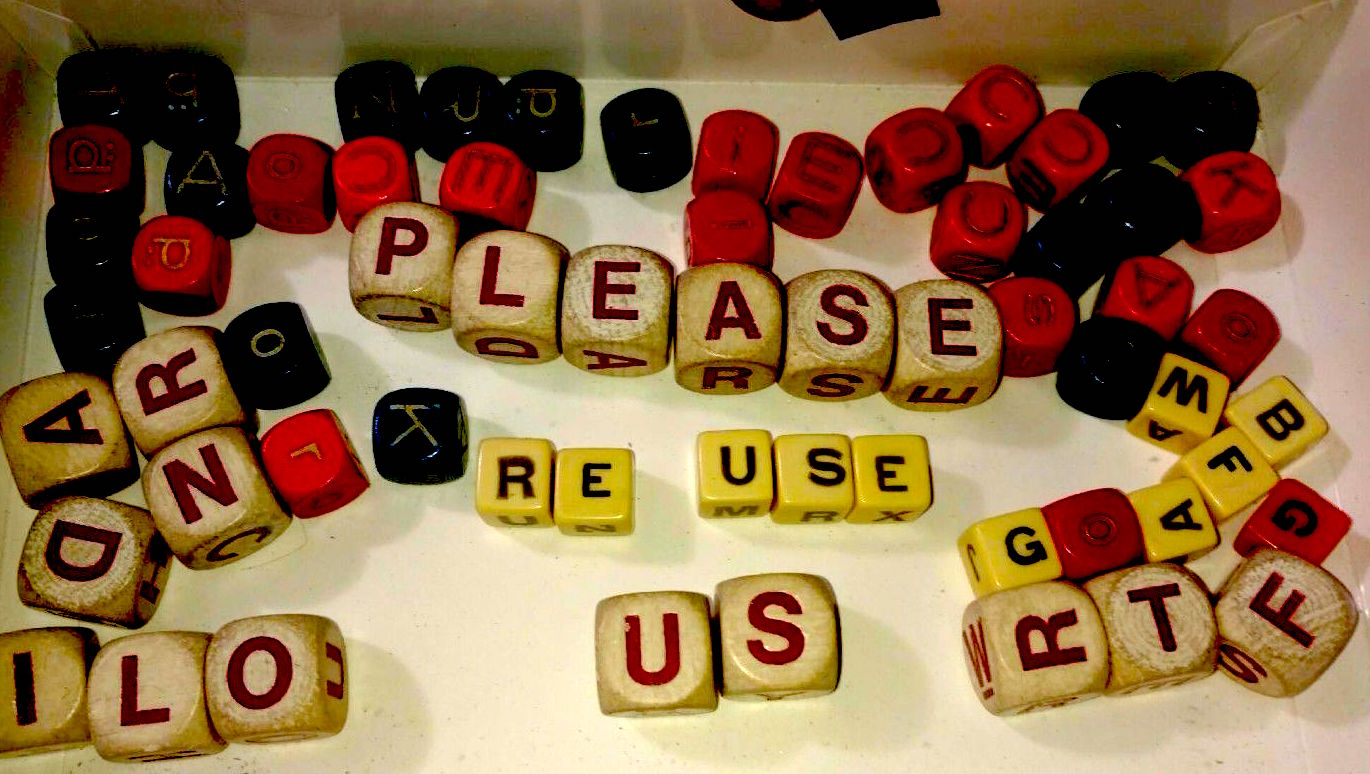

Inside are dice, too many to count, with letters printed on them. Boggle dice. Enough to fill a jumbo can of Nabob. Because the counter and table are clogged with dishes and bottles, multiple chess games on multiple boards, I throw the dice straight at the floor. They scatter across the orange-and-green linoleum, the first throw of the game.

It takes a long time for us to gather them up because we’re drunk, and laughing, and we keep finding more the rest of the night.

It’s about the first thing you see, Brad says, scooping handfuls towards me. You get rid of the letters that are meaningless and focus on a batch that speaks to you.

He makes it sound like he’s done this before, but I’m not sure if he has.

There’s a message in my pile. Sort of. It makes sense if you ignore the jumble of letters around it, or the few that squeeze into the words themselves. You push the wrong letters out of the way until it’s on its own. A sentence that rises up from the rest, and pops out like a magic-eye picture until that’s all you can focus on. Johnnie Walker helps. I can see, very clearly, that there is a part that speaks to me directly:

GOGET ON THE ROOF QIUCK

That’s when I decide the game isn’t about telling the future but about obeying orders. You roll the dice and do what it says. Easy. Brad and I nod at each other with some militance. Then we’re on the roof, looking out on Pine Crest Trailer ark.

It’s maybe eight o’clock, and a lot of the trailers still have their lights on, or are cooking dinner and you can smell it. There are still kids out playing. It’s actually nicer than you’d expect, a summer night with the cold air just starting to come in through the trees. Something we wouldn’t have experienced if not for the instruction, the good advice. The roof is flat enough that we can play the game up there, and one thing leads to the next and then we’re digging into a patch of dandelions in the front lawn, a neighbour watching from behind a screen door, concerned because we’re supposed to be grown men. Me with a shovel, Brad sitting on the ground with marmalade between his knees that we have to bury because somewhere in the letters he saw JAM JAR FUNERL.

When it’s over and we’ve said our eulogy for the spread and poured booze into the ground, we get back on the roof—because it really was nice up there—and keep playing. Brad rolls IMPORTNT BEARD and then he’s nodding, saying of course—we need to grow beards.

He’s smiling, and I can see that this is making him feel better, though it’s quite clear that the process means different things to both of us. Because he’s a brilliant writer and a well-spoken and educated person, all of his mysticism makes me feel conflicted. At the same time that I feel sorry for him for being gullible and stupid and believing in Dark-Age superstition, I’m usually wishing I could be like him—that I could believe what he believes and be able to make sense of the world using little wooden sticks or my birthday.

But really, the game is different from all that. It’s a game of truth or dare, only you can’t opt out of the crazy shit with truth. The only truth is the dice and what we see in them, what noun or verb or half-sentence we turn into a physical action. A purpose is all a person needs.

That first night we get on and off the roof several times, we dig that jar of jam up when we roll UNERTH IT, and go for a HIKE in the WOUDS surrounding the park. DRAW A PICTRE makes us sit down at the kitchenette and actually draw pictures like Brad says he and his brother used to do as kids (I draw a turtle and he draws a witch with a pointed hat).

The phrase PRESENTS GIVE AS makes us fold up and hand out the drawings to some children on bikes. We watch them stop, look at the pictures, and discard them in horror before tearing away.

It’s obvious to me that we’re seeing what we want to see, because the dice says PIZSA HAWAEE when we’re hungry and GO TO BED when it’s four hours until school starts and we’re so drunk we can hardly speak to each other.

I don’t mention this, don’t bother to point out the obvious, and the next day when we get up and go to school and come back home and make drinks, we take out the dice, spread them on a TV tray, and feel better about absolutely everything we’re doing with our lives.

And then it’s been months and months and we’re playing the game every single day like normal, regular guys play poker, or like we used to play chess. Even though he never calls it the game, Brad talks about it like that’s what it is, and he no longer speaks to the grand cosmic meaning behind any of it.

He still hasn’t brought his wife and kid here, still hasn’t saved up enough, and they still have long, painful conversations on the phone. I know she’s a reasonable, caring person, but I can hear her screaming on the other end sometimes. When I hear it from behind his bedroom door, I have to put on a record, or else take a walk through the trailer park; go buy a newspaper or a hotdog at the canteen.

For weeks it’s just him and me at the Formica tabletop, smoking pipes, growing our beards out, talking about our days, our lectures and students. And, of course, tossing the dice, our conversation pausing long enough for us to work out that we have to find a bridge (UNDRA BRDGE PLEASE).

Then it’s us talking about department heads and how hot Jane the secretary is, except we’re standing under the causeway we drove to, rolling dice on the hood in the pouring rain as traffic goes past.

Every now and then something comes up and pauses the normal flow of things, slows down the pace of the game. Makes it seem like less of a game, or more than one. Lots of rolls produce idiotic, impossible non-actions like ALWAYS BEET BALLS or SIMPLE CORD PUG FENCE.

But every now and then it would get heavy.

We’d roll something like:

WRECK A CAR

Then we’d have to consider how far we were going to take things, and who else we were going to include— as a victim—in our hobby. We’d have to decide things, sitting in our cramped little office. Have to choose which car sitting in the parking lot was going to get it. Was it better to smash a new car that probably had insurance for this kind of thing, or one that was already falling apart? Or one somewhere in between? Or a totally random selection? And where were the security cameras, anyway?

Before he took aim at the Don’t Drink & Drive Community Shuttle Van with a piece of cinderblock from the bushes, Brad noted:

It’s amazing how much your answer says about you, you know? Once you really commit to actually doing it?

Another time, months later, we roll

NOW HURT EECHOTHR

and have to decide exactly what hurt each other means, what the gravity of a wound would have to be for it to work. Though this language is a bit disconcerting, “working” really just means we could move on, that it would prompt another roll of the dice. This was an unspoken rule. We both had to be satisfied with the outcome to continue.

That night another professor comes by our office, and we talk to him with bleeding hands behind our backs, eight staples each (to match up, we figure, with the sixteen letters that made up the phrase). He’s a Shakespeare scholar named Gillis who’s been here for years and years and we’re uncertain about our standing with him.

We are, as we usually are at this hour, drunk.

What’s that now, he asks, pointing to the letters strewn all over the little table between our desks.

It’s a brainstorming tool, Brad says immediately.

I can see that he wants to keep both our game and his out-there new-age mysticism to himself.

Like Burroughs, Gillis says to us.

Like cut-ups, I agree.

Our jobs are more or less the result of being published at an extremely young age, of both of us having found critical success with our first novels. We’d supposedly been hired to revitalize the creative writing program. Actually, they hired me, and their hiring him was the result of my constant nagging and lobbying and recommending on his behalf—an agreement going way back, the kind of watchout-for-your-bros pact that you make as passionate young men (without thinking)—a campaign that barely even worked.

It’s different for me because I am in the full-time union. I bluffed my way through a dissertation, which meant there was room for me in the collective agreement. Brad has none of that. He has his novel, six good reviews, and an award. He’s on a fixed-term contract that’s quickly running out, and he’ll never be anything more than part-timer no matter what he does.

Whenever there was pressure on us from any direction in the department, we’d always fall back on our writing. It was our excuse for being late, absent, and for drinking. It always worked because no one else was a writer. Plenty wrote, sure, but they hadn’t done what we’d done. Of course, four months into the game, we hadn’t written a thing. We had found something else.

You actually get something out of this? Gillis asks.

He pushes around the dice with a pen and we both look at each other. Another unspoken rule, being broken before our eyes. Only we can do it.

Then he says he wants to try one and we have no other choice but to walk him through it.

It’s awful to watch him fill up the cup and give it a spin, awful to watch the letters and words come out. By this time we know exactly how to read them, and we almost always see the same thing, and see it right away. He’s doing it all wrong, picking through the letters to put them together like it’s scrabble, while the real message sits there in a string, as clear as day.

TELL THE TRUTH

Gillis leaves after that, saying that he hopes he gave us some good material, and we’re left to contemplate the universe and what exactly it wants out of us. It’s a long time before we look at each other. I don’t think of things like he does—and pride myself on it—but this time, I can feel it.

I can feel something heavy in the room, something old and scary. It’s the kind of feeling you got when you were a kid, at night. I wonder if this is what Brad feels like all the time.

I go get a Coke from the machine downstairs before we get started. I pour it into my Johnnie Walker, swish it around in the bottle. Brad’s sitting on top of his desk, Indian-style.

Maybe this is how things get better, he says.

Am I going first or are you? I ask him. I know right away what mine is.

He says, looking in my eye: I think this is the process by which we escape the doom.

It almost makes sense, which I don’t like. I feel a frown cross my face so I look away from him.

He is supposed to be the clown in my life. No wisdom should pass through his lips. Likewise, I am not supposed to be on this side of things. This side is his.

Like the twelve labours, Brad says. The dice are like the twelve labours. Except, you know, way more than twelve.

I ignore him and go first.

Give him the one fact I have kept to myself until this moment: I tried to kill myself.

Clear my throat. Continue: Three times.

First two were maybe not-so-serious. Last one I woke up in a hospital.

He’s quiet for a moment, and looks at me. I clarify: No one knows that. My parents don’t even know.

Brad nods. Pulls at his beard while I talk. Stays silent.

I said I’d give myself one year at this. If it didn’t work out, I’d do it for real.

Brad studies me some more and lets me have another moment.

It feels like the more words I let out into the air, the more I need to follow them. I go on for a while longer, and explain a few other things I’ve never said to anybody. How I’ve always sort of wanted to die, and that I’ve never really wanted any of the things I’ve worked for in my life, and that a supreme sense of feeling like a fraud has been following me around since I first succeeded at something simply because I was expected to. How I dream about the pressure from my father being lifted by any means, including death. His or mine. How I sawed off the barrel and stock of the shotgun I bought online because if I ever get the courage, I didn’t want to have to fire it with my big toe like Hemingway did.

Eventually I stop and Brad gives me his hard nod.

His is short and sweet, and isn’t totally unexpected. He must have decided on it right away, like I had.

He says: I resent you.

He doesn’t add more to it, doesn’t try to explain it, and I don’t ask him to.

It takes a lot not to judge him for it. But I just do the same thing he does. I don’t say anything. I listen. I let it sink in. Let it make sense, which of course, it does. He was given something he didn’t quite earn. A part-time position that he had to leave his family for. A job he didn’t want, but couldn’t pass up because of the money. A job that interrupted his life and put him and me in this situation and made it so he couldn’t do any real writing anymore. A job that made him drink again.

The two of us look at each other for a long time. I had been thinking about what the game meant, why I was playing it, and I thought I had figured it out. It’s about being unable to predict—to any degree— what is going to happen. It’s about how the dice have never, ever said:

GO ORGANIZE A LESSON PLAN or

JOIN THE LACROSSE TEAM AND LEARN CLARINET TO IMPRESS ADMISSION OFFICERS or

MEMORIZE CHAUCER

The office is a small, ordinary place, overrun with our books and dust and a couple of houseplants, a room too small for one man, let alone two, and it seems like the last place in the world anything meaningful might happen.

But I can feel that same sensation, stronger than ever.

I think of the drawings on the can, the littlefigures with horns and faces like owls or dogs. There was one that had either a mushroom cloud or a tree for a head. I imagine they’re here in the room with us, like little lords of chaos.

I lean forward and the two of us shake hands, like we’re meeting again for the first time, this transgression behind us. Our hands are still full of staples, like strange new jewelry. We don’t speak for the rest of the night, we just roll the dice and complete our tasks. Actions are our words. A conversation of small movements and tasks. Every gesture is a symbol with greater meaning beyond anything we can conceive. We communicate nonverbally, like gorillas.

Roll the dice and stare at the results, then make them real:

He and I, driving to his house to get a can of sky blue paint for the office.

He and I, dancing to Huey Lewis on the radio.

He and I, eating every bag of chips in the snack machine, forty-four bags of various flavors that I buy for a dollar a bag.

He and I, climbing the tallest tree on campus, in the dark, hoping no one sees us. Standing on icy boughs in our slacks and loafers, smoking our pipes and growing our beards out, paint on our hands and slacks and faces. Watching young girls wearing practically nothing go in and out of the campus bar.

He and I, brand new men, a new kind of man.

I feel like a mystical creature, like a Sasquatch or a yeti. I feel like what I imagine a true believer must feel like.

Late into the night, Brad—balanced in the pine tree with his feet alone—speaks:

I’m glad I have you along for this.

I haven’t spoken for so long that I find it difficult to choose my words, but he speaks again:

Those girls are some fucking hot.

He sways along with the tree.

I move back into the apartment once Brad’s family is together again.

It takes longer than it should, mostly because of the dice roll BUY A NEW STOVE, which Brad actually went and followed through on, throwing away four hundred dollars one week before he was set to meet his monetary target.

I help with the move-out from the old trailer, the move-in to the new one, and the unloading of the giant truck with all the stuff from their old house. I’m there for drinks and dinner among their boxes and stacked furniture and am witness to a Brad that I don’t fully recognize.

This one has a four-year old boy in his lap, a not-unbeautiful woman, sometimes holding his hand. Of course, I always knew it was all there, but I hadn’t expected it to be something that made me feel happy to see again.

Happy and guilty, because I know I was party to behaviour that was no doubt unfitting for a husband and father of a young child. But I can already see a change in his face and posture that tells me things are going to be different. And they are different. When the family arrives, that first night is the first night in months that we don’t play the game; that we don’t do ridiculous, boyish things and shout and smoke so much that our lungs burn and tingle. It marks the first night that we have a conversation without alcohol coursing through our veins.

The next day I’m at my apartment without thinking about it, unconsciously deciding that I am going to stay there from now on, and not see Brad unless I’m invited out.

And that’s it. Square one, reset to zero. Pressure building back up. There are forty answering-machine messages from my father. I’m alone for only a few weeks before I change things.

Jane the secretary is sleeping over, the Jane who gives us our mail and takes our messages. The Jane who hung around our doorway a few too many times until she was party to the unprofessional behavior mentioned in a few menacing notices not explicitly written to us, but for us nonetheless. The Jane who doesn’t need makeup or wild outfits to impress anyone. Jane, maybe the most practical woman I’ve ever been with, the kind of woman I might need to fulfill my own expectations of myself.

Brad gives me a clutch of dice taken from the main cup. Sometimes I push them around my desk when I feel stalled or bored, trying to find a specific word or sentence or sentiment. I’m actually working on the stories I’m supposed to be writing while I teach my courses, actually coming up with good stuff again.

Once, I consult with the dice and come up with an entire paragraph out of that black-and-white mess. I can see the letters in between the ones that are there, in the space between things. It’s a skill I’ve learned, to be able to tilt my head and make real on the hard table what was only just in the soft uncertainty of my mind. The messages are clearer and more concise than ever. Even with fewer dice, I’m getting more out of them than I should. I work hard not to roll them with serious intentions, and do my best not to start playing again, but this only lasts a week or so.

GET HOOKER TONIGHT

I don’t think the dice say this, but it is what I read, what I hear. Things are becoming predictable again. Jane and I out on dates, Jane and I at my apartment or hers. Going for long country drives with my reinstated license. Brad and I having quiet, reasonable conversations about books and government grants. Eating healthy, calorie-wise meals at the staff dining hall and lifting weights or else jogging on treadmills, side by side at the gym.

Brad is different with me now. He calls me man in a way he never used to. And he makes an effort to read all of the stuff I’m writing and give me extensive notes that are usually three or four times the length of the original work. There’s a mutual sense of establishing distance, trying to build lives more separate from one another. Our relationship with the university becomes our primary context for interaction, and we start doing the things we were supposed to be doing in the first place— hosting literary events and rooting through the slushpile for the journal, giving public readings. It would all be tedious, except that we have each other during these deeply shitty times.

UNDRESS AND STAND IN WINDOW

Jane has not found the shotgun or the box with the shotgun in it, or if she has, it has not been mentioned. I have thrown out the box of ammo, but the thing is still in the desk, under my thesaurus and dictionary and Norton anthologies. It’s more of a souvenir now, anyway. A reminder of what it was like before the game. She calls the game my creativity dice.

She is always asking why don’t you ever have Brad and his wife over?

I see enough of that guy, I tell her.

It’s true, but it is really about trying to straighten up for a while—something he is trying to do too. I know, when I see him and Ade, that there is a strain between them, or at least some kind of pain that is only half-mended. She looks at him with the eyes of a woman who wants desperately to trust her man, who has nothing but hope that he’s going to get it together. Faith. I know it has to do with how long it took for him to save his money, with the fact that his son had to endure his first semester of junior kindergarten without his father, but also that they have been apart for too long. He doesn’t grab at her tits or ass when she’s going by, doesn’t howl at her like a werewolf anymore.

This, to me, means they’re taking it slow.

DRESS AS GHOST ROAM HALLS

At the gym, Brad does chin-ups. He can do four sets of twenty-five in a row for a total of one hundred. His upper body is swelling up, he’s totally stopped drinking and smoking, and has rededicated himself to his wife and son. He tells me he hasn’t gone to the Indian casino either, though he is seeing a shaman for a very small fee. He’s happy again, that doom and gloom gone from his face. His beard is gone too, while mine has reached Karl Marx- and is approaching Charles Darwin-proportions.

Brad tells me that we broke the curse. That it’s lifted because of the game.

I’m back, he says.

Everything’s going to be all right from now on, he says. I’m through it.

Then he lifts himself up, again and again and again.

It’s a nice thought, but it isn’t mine. It’s nice to have him back where he was, to have him strong and stable, and not to have to worry about him anymore. I expect him to ask me if I’m still playing the game, but he doesn’t. I’m not sure if this is because he knows I still am, or if he assumes that because things are better for him, they must be better for me.

BREAK WRIST WTH HAMMER HA HA HA

It’s necessary for me to play, because there’s still the matter of all the things that are waiting for me, things that I and everyone else are expecting down the road. If not success, I’d call it excellence—full-spectrum excellence in all aspects of a modern, Western existence— the weight of which was lifted for a period of time, and is now back on, in full force, even worse than before. My father calls and I respond to his questions using the curriculum vitae I have drafted to send to an agent, and from my leather-bound agenda with details of readings, lectures, and important research for my novel.

I need it.

DRINK COCAINE MILKSHAKE

I live up to my expectations not in spite of the game, but because of it. There’s a mental calendar in my head for work, for writing, and for Jane. I fill hers up with important, seemingly spontaneous moments, all of them leading up to a road trip home with the new dog, to meet-and-greet with Mom and the old man. Real, sincere sexual contact is peppered throughout. If her formal introduction goes well, there’ll be six more months of carefully manipulated events before a ring is produced in a highly specific way, just for her. It will be at a campus hockey game, where the team will skate out with different pieces of a large sign, black letters on white board, coming together: MARRY ME JANE. I can feel each event leading into the next, just like words turn into sentences, turn into paragraphs—each page a perfectly measured construct. A marvellously complex and dazzling endeavor, and what would be a deeply bogus one, were it not for the spirits or forces that deliver the messages to us from the great beyond.

RUN INTO WOODS BAG ON HEAD

ABOUT THIS STORY

I wrote THE GAME somewhere between 2011-2012 and published it with PRISM INTERNATIONAL in 2013. I have always really liked it, both for its characters and the cosmic-message-as-centered-text-gimmick. My editors have both pointed out that I am notorious for becoming enchanted with characters, even to the point where I no longer talk about them as my creations. They're just little people delighting me with their weird behaviours. This is a fair assessment, though for this story it's a little different.

You'll notice early on that the characters in this story are obsessed with playing chess. Though I am thoroughly no good at it, chess was, at this period in my life, a major part of my daily routine. The very talented Ryan Paterson--who helped me with this story and many others, and whom BAD THINGS HAPPEN is dedicated to--and I always had a game going, either on a real board or in our phones, and it was a much needed distraction. But we also had other, stupider games we engaged in, like playing horseshoes at midnight (roaring with delight when the metal-on-metal contact between the post and horseshoe produced sparks in the darkness), and drinking as much as we could stomach virtually any night of the week. THE GAME represents this same kind of boyish time-wasting, but coupled with a scarier kind of desperation we had both left behind years ago. It also touches upon obsessions of mine from years before, like the occult, conspiracy theory, and larger delusions about the universe and its meaning.

Most of all, this story represents a kind of love letter to my friend, a person who has always been there for me, and who has always let me act like a complete clown (I'm sure you can tell who is who in the story). This piece ended up getting taken out of BAD THINGS HAPPEN, probably because it was a little too silly, because it eroded some of the power of the more potent story in the collection IS ALIVE AND CAN MOVE, and because its tone isn't terribly different from the other stories, but it remains one of my absolute favourites.

Thanks for reading,

KRIS